In June, Texas A&M University hosted its inaugural philosophy camp for teens and tweens. Using the Philosophy for Children program as our model, we had several pedagogical aims: to introduce pre-college students to philosophical thinking and dialogue; to develop an intellectual community among the campers; and to provide a space in which young people could engage as equal partners in a series of spirited philosophical discussions.

Our camp enrolled a diverse mix of forty-six students, who were evenly divided between high school and middle school, with approximately equal numbers of those identifying as females and males in each age group. Roughly a third identified as non-white, the rest as white/non-Hispanic. Half–regardless of ethnicity or gender–identified as academically inclined toward the STEM fields. Although most of our campers were from our local community in Bryan-College Station, Texas, we had several enroll from other cities in Texas (Dallas, Austin, Houston, and beyond), a few from outside Texas completely, and one from Paris, France.

In other words, the demographics for our camp do not match the demographics of the profession. Data gathered by Kate Norlock on women in academic philosophy in the United States revealed that, as of June 2011, “roughly, among full-time instructional faculty, women are 16.6% of the 13,000 total full-time philosophy faculty (that is, 2,158), and 26% of the 10,000 part-time instructors (that is, 2,600). In other words, women are 4,758 of the 23,000 or so: 20.69%.” The numbers and percentages are significantly lower for philosophers who identify as non-white. Working with the camp, in which students identified either as oriented toward the STEM fields and/or as non-white or not male (and nearly every student fell into one category or the other, or both), we found a very different picture of philosophical community and dialogue. Our experience with the campers reminded us that philosophy is interesting across lines of gender and ethnicity.

We organized the week around themes that we thought would be of particular interest to pre-college students while also providing a broad view of the discipline. We asked: What is philosophy? What does it mean to be ethical? What makes a society just or unjust? What is the ideal form of education? What is art?

Beginning each day with a reading from Plato, we engaged the campers in lively discussions about the history of these ideas and their continued importance for contemporary society. The campers connected Plato’s questions from 2500 years ago to difficult and often painful problems such as police brutality, gender socialization, surveillance, and socioeconomic inequality.

On the first day of camp we introduced Plato’s cave allegory and his contention that various epistemic chains prevent most human beings from turning toward the truth. That afternoon the middle schoolers contemplated the nature of their own chains in a discussion of gender equality. The middle schoolers concluded that there were not relevant differences between the sexes. One of the counselors then asked, “How is this classroom organized?” After a long pause and some glances around the room, the knowing smiles emerged. Both the boys and the girls were clustered throughout the room…as boys and girls. “Can boys and girls be friends?,” one camper asked. “What are we assuming by asking this question?,” queried a counselor. “Maybe gender differences are more complicated than we normally like to admit,” one eleven-year old girl observed. “Maybe these are our chains.”

In a session with the high school students on what makes for a just society, a discussion of race ensued:

“Are natural kinds (groups that form naturally) ‘real’?”

“How do natural kinds relate to race?”

“Do parents of different races have different expectations for their kids?”

“Aren’t these stereotypes?”

“Do stereotypes have any truth to them?”

Our group of high school students raised these questions within a candid discussion about race and ethnicity. What could have been a volatile shouting match about race became the springboard for a thoughtful conversation about identity and about how to have difficult conversations.

A discussion of surveillance within the context of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a design which allows a single guard to observe all inmates within an institution, prompted one high school girl to vent about school dress codes: “[They] make me feel like I’m constantly being watched and controlled.” Sharing her view with the group, she cleared a space for other young women to voice their concerns. Guided by the question, “What are schools explicitly and implicitly teaching?,” the campers contributed their views to the larger conversation about how schools should (and do) operate.

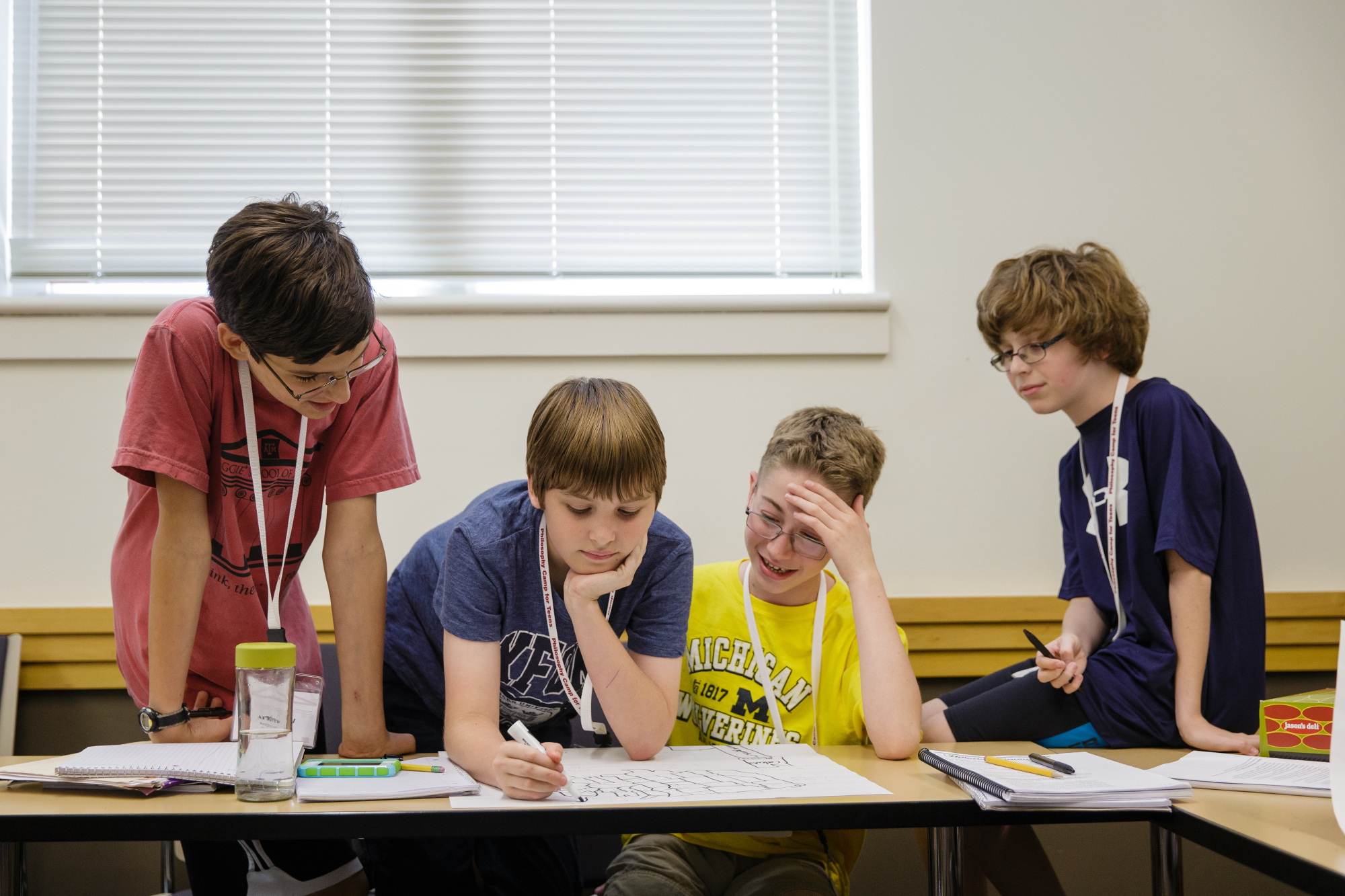

As if viewing an experience in time-lapse photography, we witnessed all the campers—but especially the young women—develop not only their confidence but also their voices. Each found a unique approach to intellectual inquiry and discussion. The safe space encouraged them to reevaluate their own positions in light of better arguments for an opposing view. Responding to our end-of-camp survey, one parent observed that her son benefitted from the opportunity to discuss how a fair society would look while offering suggestions for its design. “It does not matter,” she wrote, “if his ideas would work. The influence [of being challenged to think about this topic will] stay with him and will impact his way of thinking in the future.” Another high student shared this reflection: “After hearing what everyone had to say [about what would make educational opportunity fair], I actually realized that I had changed my mind about what would constitute a fair system. I thought it was amazing to have completely believed in something and then by the end of the day, realize that I didn’t [believe in those same ideas] anymore.”

Philosophy’s commitment to truth forms the basis of our understanding of what it takes to educate productive citizens within a democracy. As college teachers of philosophy, we often focus on sophia—knowledge or wisdom. As John Dewey reminded us 100 years ago in his landmark book, Democracy and Education, the pursuit of truth in a democratic society is best understood as a collaborative endeavor. It cannot and should not be separated or abstracted from the relationships we have with one another. Working with these young people reminded us to pay more attention to the desire for friendship through engaged discussions about meaningful ideas. These kids began the week barely knowing each other. Through the week they shared their deepest beliefs with each other and they were challenged by each other to defend those beliefs. By the end of the week, they were trading Instagram and Facebook information to stay in contact with each other. They left philosophy camp having formed lasting friendships based on the shared experience of philosophical dialogue in its ideal form: open, exploratory, curious, and playful.